Billions placed in revolving funds but little accountability

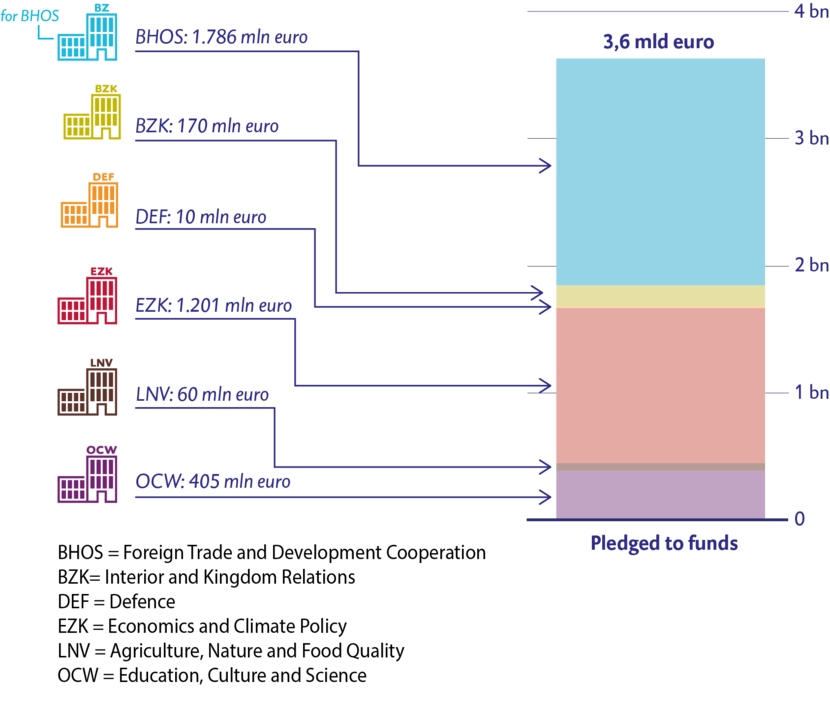

The Dutch government is increasingly using revolving funds to achieve social goals, for example to encourage domestic energy savings and promote trade with developing countries. The Netherlands Court of Audit has found that €3.6 billion has already been placed in revolving funds. But some matters have not kept pace with this means of financing. A specific minister, for example, is not responsible for oversight, the revolving funds are not subject to specific regulations and the House of Representatives receives only limited information about how much money is involved, how long the government will continue to use the funds and the results they achieve.

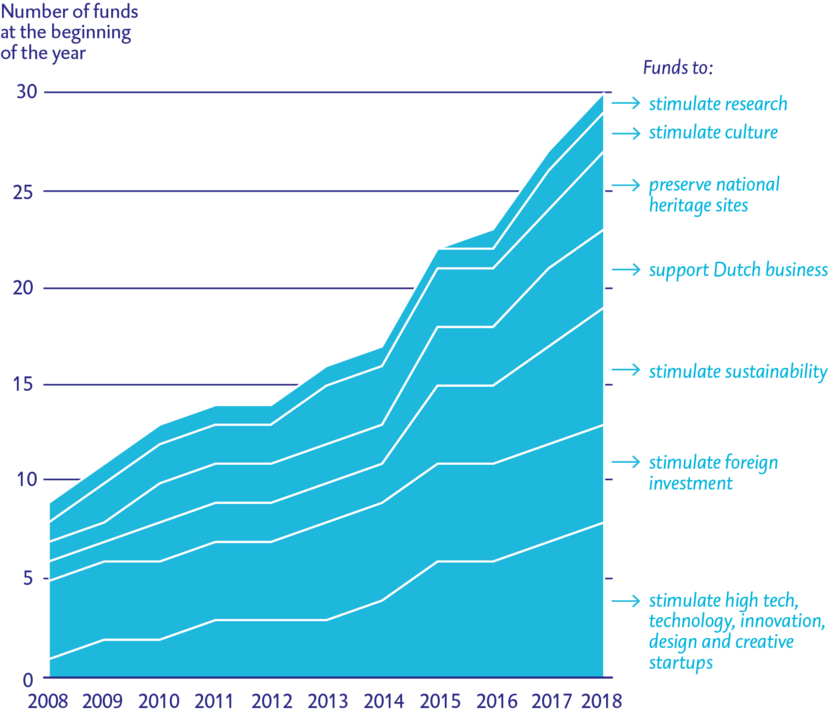

The Court of Audit has investigated the growth and size of the central government’s revolving funds and found that there are at least 30 of them. Ministers deposit money in them to carry out social projects, for example by providing loans. Income in the form of interest and repayments is returned to the funds so that the money can be used again for other projects. In theory, this ‘revolving’ nature of the funds means more effective use can be made of public money.

The Court’s audit provides a first impression of the government’s 24 largest revolving funds and explains how their democratic accountability and audit are regulated. It was difficult to gain an understanding of the funds as little information is available about them.

Central government had pledged €3.6 billion to thirty revolving funds at the end of 2017

Revolving funds are a relatively new phenomenon. Both the number of funds and the amount of money placed in them are growing strongly. The revolving funds investigated by the Court of Audit are currently worth €3.6 billion. This amount will increase further, partly on account of the establishment of Invest-NL, a national investment fund with a capital of €2.5 billion.

Central government is increasingly using revolving funds, chiefly to stimulate high tech/technology/innovation/design/creative startups, foreign investments and sustainability.

Central government is making more use of revolving funds as financing instruments. In the Court of Audit’s opinion, the House of Representatives must be informed about the funds and the results they achieve. There is currently no central insight into the number of revolving funds or why the government has established them. Neither are the funds subject to specific regulations. The House therefore cannot adequately exercise its budgetary rights. The Court of Audit recommends that a single minister should be made responsible and accountable for the structure and regulation of the funds and a separate legal framework should be established. The provision of information to parliament is also open to improvement.

The Minister of Finance wrote in response to our report that parliament’s budgetary rights and ministerial responsibility were automatically ensured because the revolving funds were financed through the budgets of individual ministries. The Court of Audit notes, however, that the multiyear and revolving nature of the funds are out of step with the annual budget cycle. Budget approval would be improved if the government made more detailed agreements with parliament on the provision of information on revolving funds.