Early application for long-term care does not increase likelihood of access

The likelihood of someone receiving care under the Long-Term Care Act (WLZ) is not affected by the municipality in which he or she lives. The Care Assessment Centre (CIZ), which deals with the cases, assesses all applications in a consistent and impartial manner and does not base its decisions on where the applicants live. If a municipality has a policy to fast track people to the WLZ, it will not work.

The Netherlands Court of Audit came to this conclusion in a recent audit of problems in the access to long-term care. The public debate has created the impression that some municipalities encourage their residents to apply for long-term care under the WLZ too quickly. This practice is known in the Netherlands as ‘bypassing’. The Court of Audit found that it had no direct influence because the CIZ consistently checks whether or not each application satisfies the criteria. The CIZ does not take personal circumstances into account when assessing applications for the WLZ. This is not the case with the social support scheme (WMO), which is implemented by the municipalities themselves.

To carry out its audit, the Court analysed applications and rejections from before the WLZ came into effect in 2015 until the end of 2017. In total, it examined 163,551 ‘first’ applications (it did not consider re-assessments). Of the applications examined, 17% were rejected. To place its findings in context, the Court also interviewed 30 experts from the care sector: municipal policymakers and implementers, client support staff and personnel from the CIZ.

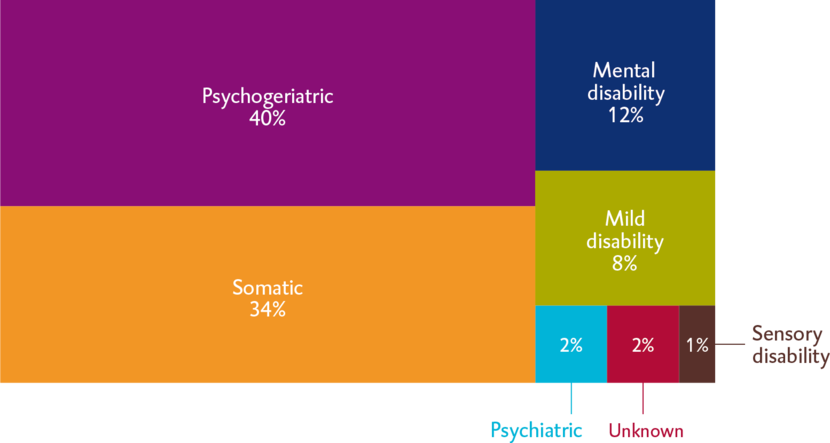

Three-quarters of WLZ applicants have psychogeriatric or somatic complaints

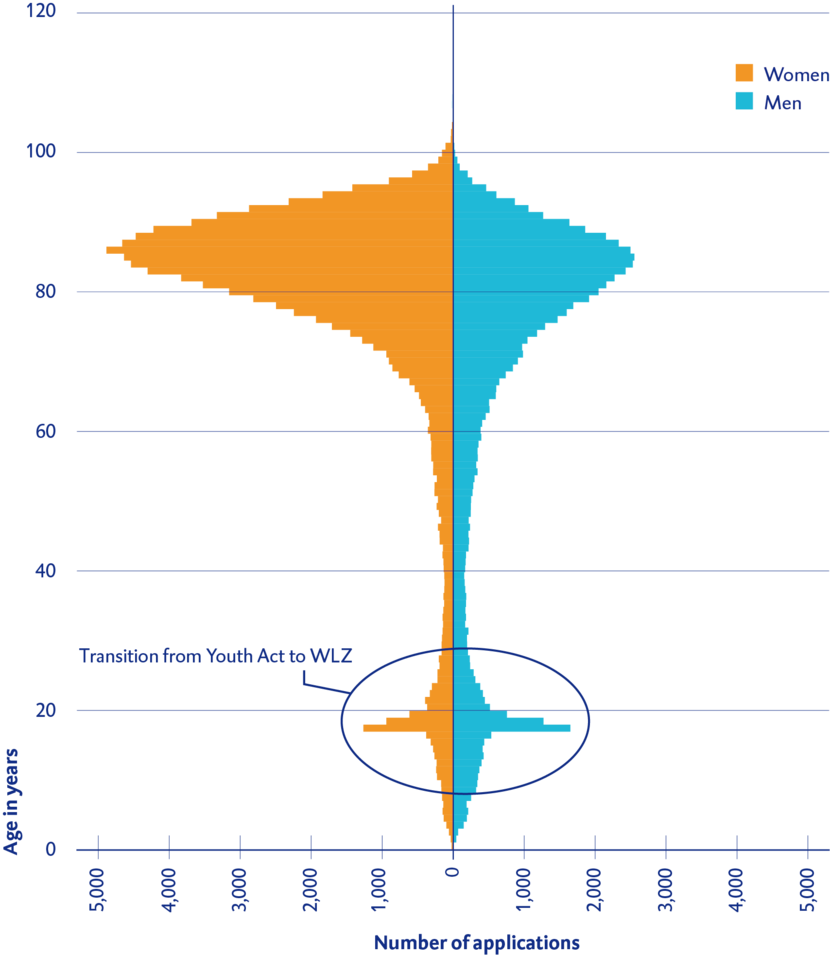

The younger the applicant, the less likelihood of long-term care

The data analysis found that the applicant’s age was a factor in the likelihood of receiving long-term care under the WLZ. The audit report states, “The younger the applicant, the less likely it is that he or she will receive care under the WLZ”. The Court of Audit also said it was “striking” that over the years it had become increasingly unlikely that young people would receive care. In 2017, 35% of all applicants under the age of 18 were refused care. In 2015, only 28% had been refused. The increase might be due to a transitional regulation that applied to young people receiving assistance under the Exceptional Medical Expenses Act.

Mild mental disability

Talks with the experts revealed that a particular group of young people were not represented in the figures. Young people with a mild mental disability are subject to the Youth Act until they are 18. Once they are adults, some of them apply for long-term care under the WLZ. But those with an IQ of around 70 are often not accepted because their applications do not satisfy the criteria. Yet these people need permanent intensive care to prevent them getting into problems. The municipalities must then find a solution for them.

Psychiatric patients

The lion’s share of the applications made by a relatively small group of about 1,300 psychiatric patients (2% of all applications for long-term care) are rejected. The Court of Audit noted an increase, however, in the number of acceptances in 2017. In that year, 30% of the applications were honoured, in contrast to 5% in 2015 and 2016. The increase was related to the introduction of a rule in 2015 that admitted people who had spent at least three years in a psychiatric institution to the WLZ scheme.

The figures highlight the uncertainty about where these people can go to for appropriate care. In talks with the Court of Audit, some municipal policymakers, client support staff and CIZ researchers expressed their concern about this state of affairs.

CIZ good gatekeeper

The audit found that CIZ performed its role as gatekeeper objectively, as intended. The assessments rejected more young people and psychiatric patients because of the statutory conditions on eligibility for long-term care. The first condition is that there must be a physical disease or disability, a psychogeriatric disorder, a mental disability or a sensory disability that requires long-term care. Secondly, it must be clear that the patient will require or be able to rely upon permanent care 24 hours a day for the rest of his or her life because a recovery or improvement in the situation is impossible. The first condition excludes many psychiatric patients from the care. The second makes it difficult for young people to receive care because their situation may improve.

Half the applicants are older than 81, with a peak around the age of 18 owing to the transition from the Youth Act to the WLZ

Help with applications helps

The Court of Audit concluded that the likelihood of qualifying for long-term care under the WLZ would improve if a district nurse or other care provider helped the applicant complete the application. They have more experience with the submission of applications and the WLZ’s criteria, and understand which medical information is important. Only 10% of applications submitted with their help are rejected. The probability of rejection is highest (36%) if the applicant receives no help from a care provider, assistant, relative or friend. The Court of Audit notes that these differences may be because people with a serious disability often receive more help with their applications.