No control of failing youth protection

The Dutch government transferred responsibility for youth protection to municipalities in 2015. Its aim was to reduce the overall cost of youth care, shorten waiting times and cut red tape for care providers. 8 years later, and the policy has still not succeeded. Children and vulnerable families do not receive the help they need when they need it. For some considerable time, the politicians concerned (the Minister for Legal Protection and the State Secretary for Health, Welfare and Sport) have inadequately borne their statutory responsibilities for youth protection. The Netherlands Court of Audit comes to this conclusion in its report ‘Organised Impotence’

The 2015 Youth Act requires municipalities to organise youth protection locally. The minister and state secretary thought the municipalities’ proximity to children and families would enable them to tailor the care provided. In practice, however, care provision is badly organised and impracticable for both municipalities and care providers. In 2019, the Justice and Security Inspectorate and the Health and Youth Care Inspectorate concluded that the situation was ‘not acceptable’. At the moment, 3 years later, there are still no signs (or expectations) of a structural improvement in the system. Children are suffering.

Youth Act took too much for granted

Youth protection measures such as family supervision orders and custodial placements are blunt instruments that can have far-reaching consequences for the private lives of children and families. Nevertheless, when the government transferred youth protection to the municipalities it did not recognise its distinct financial, administrative and supervisory characteristics in comparison with other kinds of youth care. The quality of youth protection would be safeguarded by certification, but certification checks considered only the institutions’ compliance with the right procedures. They did not necessarily say anything about quality. Furthermore, for a long time the inspectorates did not supervise the specific features of youth protection. They did not depart from their general supervisory policy. It was not until early 2019, when they received many reports and warnings, that the inspectorates decided to investigate some youth protection institutions.

Ministers late to realise that all was not well

When it transferred youth protection to municipalities, the government deliberately decided to collect only limited information on the protection provided. For some considerable time, therefore, the minister and state secretary had little insight into the practice. They had no information, for example, on the length of waiting lists, the number of custodial placements or the financial health of the youth protection institutions. As most municipalities did not carry out obligatory client studies, moreover, the ministers did not know what the children thought about the system. For all these reasons, the minister and state secretary did not realise until late that all was not well with youth protection.

Improvements snared by red tape

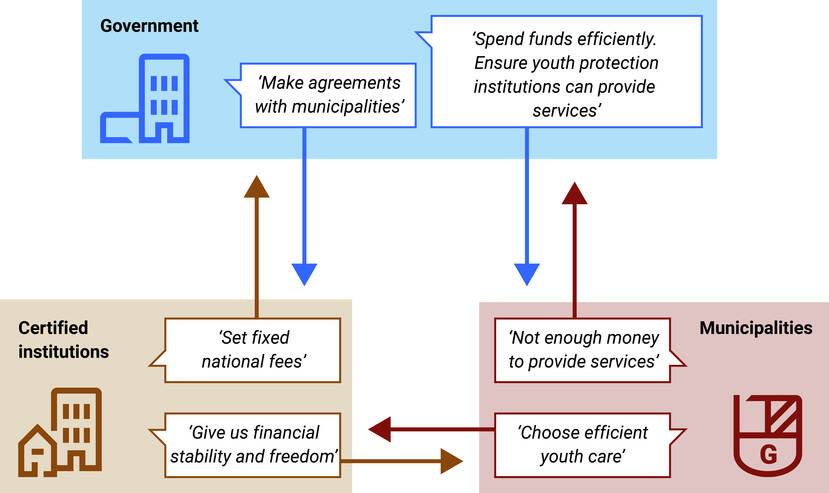

Municipalities must ensure that youth protection institutions can work effectively. As the minister and the state secretary cannot intervene directly, they have to rely on the municipalities to make changes. They have encouraged and supported municipalities but their efforts have not led to structural improvements. More seriously, municipalities, care providers and the government are seemingly powerless to take the lead and make improvements themselves. Each party depends on another to solve its problems before it is able to act. This dependency loop has to be broken. In our opinion, the minister and state secretary should take the initiative in this.

Government, municipalities and certified institutions caught in a dependency loop

Recommendations

The Court of Audit’s main recommendations to the Minister for Legal Protection and the State Secretary for Health, Welfare and Sport are:

- Clarify the minimum level of protection children can expect to receive. Lay it down in law and supervise compliance.

- Make changes in the system carefully. Bear in mind that new rules impact the people on the shopfloor. Systems do not protect children, people do.

Response of the Minister for Legal Protection and the State Secretary for Health, Welfare and Sport

In their response to the report, the minster and state secretary write that the conclusions match their understanding of youth care and youth protection. They acknowledge that many steps still have to be taken to improve youth protection and provide appropriate care. They are confident, however, that the scenario for future youth protection and the agreements made in the Reform Agenda will lead to improvements.

Court of Audit’s afterword

In view of the current state of affairs, the Court of Audit does not share the minister and state secretary’s confidence. Such fundamental issues as who is responsible for what, what powers they need and how they will be funded still have to be answered. The Court notes in its afterword that its recommendation to lay down in law the minimum protection a child can expect to receive would also strengthen the supervision exercised by the inspectorates, municipalities and central government.