Many work-related accidents not reported to Labour Authority

Some 200,000 people suffer an accident at work every year in the Netherlands. About 60 die as a result and an estimated 4,000 people die from unhealthy working conditions every year. The Netherlands Labour Authority is tasked with following up reports of accidents and work-floor complaints. It does so transparently, but our investigation of the reporting process also found that many reporting bodies failed to report at least half and possibly up to 70% of accidents.

Number of unreported accidents higher than thought

Employers do not report many work-related accidents even though they are required by law to do so. An earlier study estimated that about 50% of accidents went unreported. An investigation by the Netherlands Court of Audit, however, concluded that this was more likely to be a lower limit. The number might be significantly higher, perhaps as high as 70%. This was not known until now.

The Labour Authority and the Minister of Social Affairs and Employment (SZW) are failing to increase employers’ willingness to report accidents. Possible causes may include ignorance of the obligation to report accidents, uncertainty about the seriousness of accidents and fear of disputes and litigation. Dangerous working conditions accordingly remain unknown to the Labour Authority and it is unable to optimise safety at work. Temporary workers and labour migrants are at particular risk of work-related accidents. A double reporting obligation will come into force in 2024. Both the hiring organisation and the temporary employment agency will then be obliged to report work-related accidents to the Labour Authority. This obligation is designed to reduce the underreporting of accidents involving temporary workers and labour migrants.

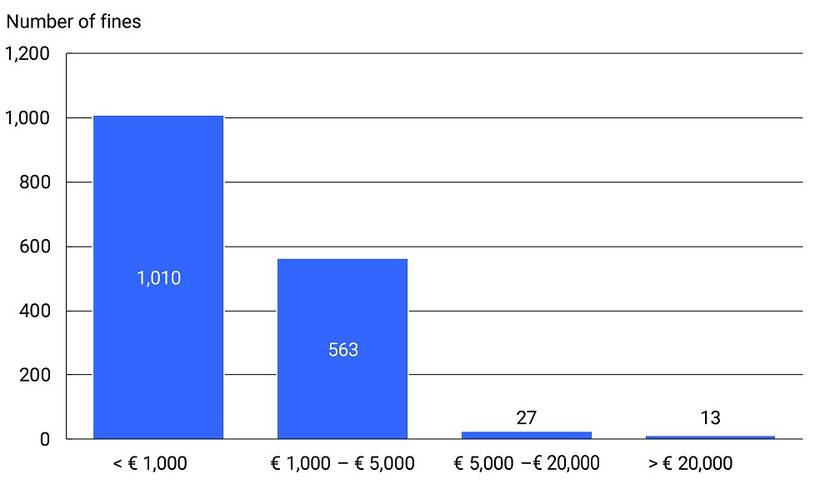

Maximum fine for not reporting accidents rarely imposed

Until 2013, it was more advantageous for employers to pay a fine of up to €4,500 than to report an accident. To discourage underreporting, the Minister of SZW increased the maximum fine to €50,000. In practice, the Labour Authority rarely imposes the maximum fine for the underreporting or late-reporting of an accident (only 3 times in 7 years). The average fine is €1,500.

Fine for not reporting or late reporting rarely approaches €50,000

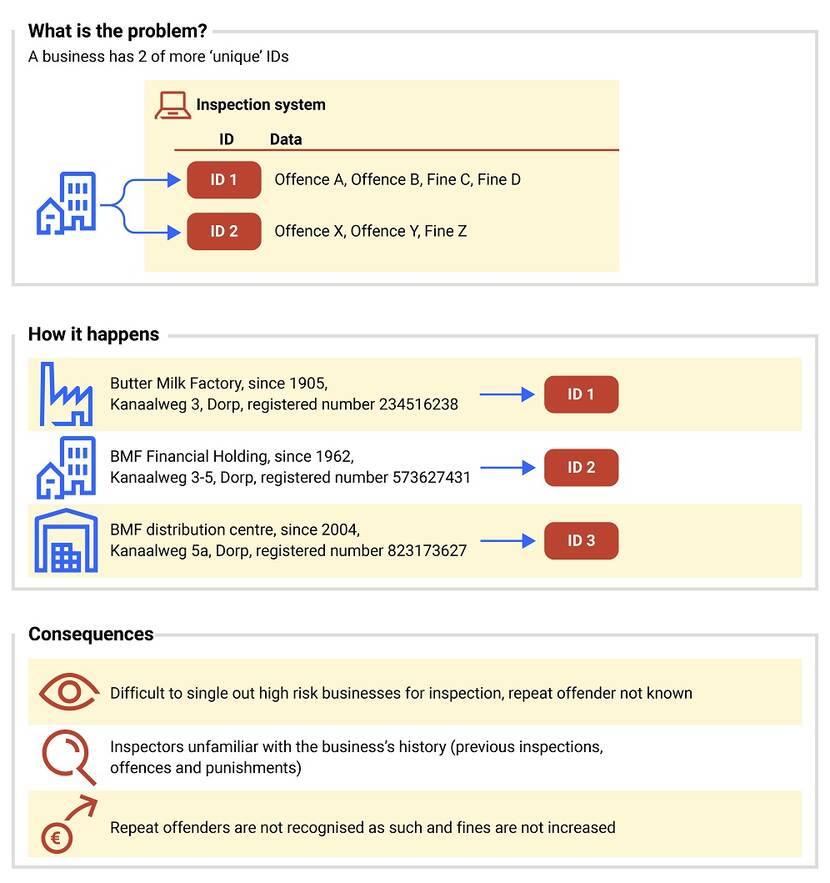

Multiple records muddy insight into repeat offenders

The way in which the Labour Authority records businesses in its inspection system makes it more difficult to identify those that repeatedly break the law. The Authority sometimes uses several identification numbers for a single business. It therefore does not always have the insight necessary to spot repeat offenders and there is a risk that fines will not be increased in accordance with the law. How this affects the Authority’s effectiveness is not known.

Some businesses entered more than once in the inspection system

Consequences

Difficult to single out high risk businesses for inspection, repeat offender not known Inspectors unfamiliar with the business’s history (previous inspections, offences and punishments) Repeat offenders are not recognised as such and fines are not increased.

Follow-up investigation

We consider the Labour Authority’s enforcement of the Working Conditions Act in more detail in our report on the Ministry of SZW’s 2023 Annual Report, forthcoming on 15 May 2024.

Background to this investigation:

Some 1,600 people work at the Labour Authority. Its annual budget amounts to €200 million, rising to €210 million in 2025. The Labour Authority applies this money not only to improve health and safety at work but also to combat labour exploitation.

Between 2016 and 2022, the Labour Authority received about 60,000 reports, 47% related to accidents and 53% were complaints. A relatively high number of the reports involved falls and contact with machinery, for instance a roofer who fell from a roof when fitting solar panels or a factory worker whose arm was caught in a machine.

Like all other inspectorates, the Labour Authority has to decide which reports it follows up. Its choices are transparent and underpinned by clear criteria. We also found that the Labour Authority identified trends in the reports and used them to set priorities and make risk-based supervisory decisions.