What is the European banking union and will it prevent a future banking crisis?

The banking crisis of 2007 and 2008 laid bare vast inadequacies in the structure and practical supervision of domestic financial institutions and the financial system. It also revealed shortcomings in risk management at a large number of financial institutions. Many of these operated across borders, and the national supervisory mechanisms were not designed to handle the strong interlinkages between European financial markets. As a result, the governments of many countries were forced to intervene to prevent the financial system from collapsing. In the Netherlands, the Dutch government intervened in systemically important banks such as ABN AMRO, ING and SNS (renamed in 2017 as de Volksbank). This had huge repercussions for the national budget and, by implication, taxpayers.

European measures to prevent a new banking crisis

Ever since the start of the crisis, EU officials have discussed ways and means to prevent repetition. In May 2009, the European Commission proposed a series of reforms to create a new institutional supervision framework. The new European System for Financial Supervision (ESFS) came into effect in January 2011.

The ESFS encompasses macro- and micro-prudential supervision. Macro-prudential supervision is concerned with preventing and curbing systemic risks to financial stability emerging from macro-economic developments. The European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB) plays a central role in macro-prudential supervision.

Micro-prudential supervision aims to limit the risks posed to individual institutions. Micro-prudential supervision is performed by several European sector-specific authorities, one for the banking sector, a second for insurance companies and occupational pension providers, a third for securities institutions and markets.

The European banking union

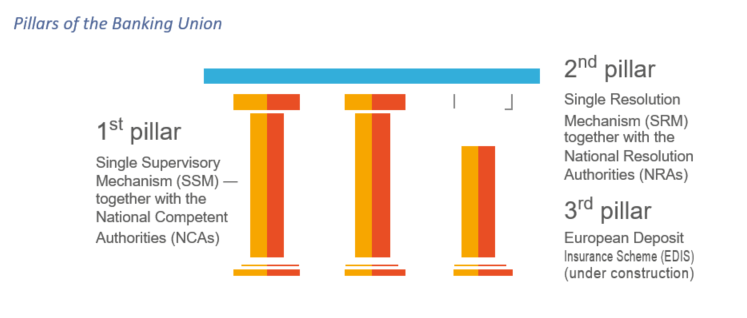

The launch of the European banking union in 2012 marked the most important step taken by the EU to prevent a new banking crisis. See here for more information on the banking union.

The first pillar of the banking union is the supervision of banks. The Single Supervisory Mechanism is an arrangement between the European Central Bank (ECB) and the national supervisory authorities in the euro-area. The ECB has taken over responsibility for the supervision of significant banks, i.e. banks with a balance sheet total of at least €30 billion, from the national supervisory authorities. National supervisory authorities are responsible for supervising all other financial institutions, e.g. medium-sized and small banks in their respective countries.

The Single Resolution Mechanism (SRM) is the second pillar of the banking union. It was established to ensure the effective resolution of euro-area banks that find themselves in serious financial difficulties, without national governments or taxpayers having to foot the bill. One of the resolution tools available to the resolution authorities is a bail-in. In a bail-in, shareholders, bondholders and savings deposit holders (with savings exceeding €100,000) bear their share of the losses arising from the failure of the bank. Another option is to sell the failing bank, either in full or in part. As under the SSM, a European organisation, the Single Resolution Board (SRB), is directly responsible for the resolution of significant banks in the euro area, and national resolution authorities are responsible for the resolution of medium-sized and small banks in their own countries.

A Single Resolution Fund (SRF) financed by euro-area banks was established in 2016. Its resources can be used to resolve banks in financial trouble. The ambition for the end of 2023 is that the SRF will be worth 1% of the value of the eligible deposits held by the participating banks, estimated at €80 billion by 2024. The fund was worth €66 billion at the end of 2022.

In addition, the European Commission is planning to set up a European deposit insurance scheme. This is the third pillar of the banking union to protect European savings deposit holders up to a specified amount. Although the European Commission tabled proposals to this effect in November 2015, they had not been approved by the EU member states or the European Parliament mid-2023. Until they are, the European deposit insurance scheme remains a matter for national authorities only.

On 18 April 2023, the Commission presented new proposals to strengthen the rules on problem banks. The objective is to prevent governments having to step in to save ailing banks using taxpayers’ money. As several member states had difficulty with the proposals, negotiations are expected to be difficult and protracted.

Recapitalisation of banks by the European Stability Mechanism (ESM)

Since 2012, the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) has offered a means to recapitalise banks indirectly. The ESM is a permanent emergency financial assistance fund providing loans to EU member states that run into financial difficulties. In an indirect recapitalisation, a government applies to the ESM for aid, which it passes on to banks facing financial difficulties. Spanish and Cypriot banks have been recapitalised in this way. In June 2014, the Eurogroup agreed to create the option of allowing failing banks to borrow money from the ESM without government intervention. In other words, it created an instrument for the direct recapitalisation of banks by the ESM, which has a maximum recapitalisation capacity of €60 billion. The instrument can be used if a bank fails to meet the ECB’s capital requirements (or is likely to do so in the future), and if this poses a grave threat to financial stability in the euro area. Another condition for the use of this instrument is that all other private and (national) public remedies have been exhausted. Click here for more information.

On 4 December 2019 the Euro group decided that the ESM could also serve as a backstop for the Single Resolution Fund (SRF). The ESM treaty has been adjusted accordingly. A backstop means that if SRF-resources are exhausted, the ESM can lend money to the SRF to finance resolution. This new mechanism will come into effect on 1 January 2024. The maximum loan capacity is set at €68 billion.

More information about ESM as SRF’s backstop

Situation in the Netherlands and audits by the Netherlands Court of Audit

Since the introduction of the European banking union, significant banks in the Netherlands have been supervised by the ECB in conjunction with the Dutch central bank (De Nederlandsche Bank, DNB) as the national supervisory authority. DNB remains responsible for the supervision of medium-sized and small banks in the Netherlands. We audited DNB’s supervision of these banks in 2017 and found that it is well organised. DNB’s supervision is intensive and strict. Where banking supervision is concerned, the Ministry of Finance does not exercise all its powers as DNB’s supervisor.The introduction of the Single Supervisory Mechanism for banks has impeded supreme audit institutions’ ability to independently audit banking supervision. Click here for more information.

We worked together with the supreme audit institutions of Cyprus, Germany, Finland and Austria and published a joint report on the European banking union.

We also audited DNB’s preparations for the possible failure of medium-sized and small banks, and published our audit report in 2019. We found that, although progress had been made with resolution planning for medium-sized and small banks, not all plans had been completed. Since March 2019, DNB has prepared and endorsed resolution plans for the vast majority of Dutch medium-sized and small banks. The plans comply with statutory requirements, but are brief. We also found that the Minister of Finance, who is responsible for supervising DNB’s resolution activities, does not fully supervise DNB. As a result, he does not have up-to-date information on the general state of resolution planning for medium-sized and small banks in the Netherlands. Precisely because DNB is still in the process of fleshing out its role as the national resolution authority, we had expected the minister to play a more active role in supervising DNB’s resolution activities, also in the light of his responsibility for the stability of the financial system and his role as the national treasurer.

We performed this audit in conjunction with the supreme audit institutions of Austria, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Portugal and Spain. A joint report on resolution planning was published on 16 December 2020.

The European Court of Auditors published a report on reslution planning on 14 January 2021.

Impediments to independent audits by supreme audit institutions (audit gaps)

The European Court of Auditors (ECA) has only limited access to the European Central Bank (ECB), the European supervisory authority. This is because the ECA’s mandate is limited to auditing the ECB’s operational efficiency of management, which in the ECB’s opinion excludes the actual supervision of banks. Supreme audit institutions in the euro area with a mandate to audit the supervision of and preparations for the resolution of medium-sized and small banks are also facing more restrictions on their access to data. These are commonly referred to as ‘audit gaps’. This applies particularly to the ECB, which does not share information with supreme audit institutions. The Single Resolution Board (SRB) also restricts the access of supreme audit institutions to the information they need for their audits. In addition, the supreme audit institutions of ten euro-area countries have either no, or an only limited, mandate to audit the supervision of medium-sized and small banks.

In August 2019, the ECA and the ECB reached agreement on a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) to improve the ECA’s access to ECB information. Click here for further information.

We consider the MoU to be a meaningful first step towards improving the independent external audit abilities of supreme audit institutions. Although the ECB seems to have become less reluctant to release information, the MoU bridges only some of the gaps that we identified supreme audit institutions' ability to perform independent external audits of prudential supervision. Not only has the MoU not altered the ECA’s limited formal mandate, the ECB also reserves the right to ask the ECA to explain why it has requested certain information. In a national context, this restriction does not apply to our audits of DNB’s prudential supervision of medium-sized and small banks. Furthermore it is not clear what implications the MoU has for the rights of supreme audit institutions to access relevant ECB information, as the MoU does not say anything about this.