As a partner country, the Netherlands contributes to the investments in the development and production of the JSF and in the creation of a worldwide maintenance network for the JSF. These contributions are analysed below.

Agreed contributions for each MoU

The Dutch government agreed in 1997 that the Dutch Ministry of Defence would contribute USD 10 million towards the design phase (CDP) of the JSF programme. This equates with €10.5 million (in 2017 prices). The Ministry of Economic Affairs also made a contribution, viz. of €82.8 million (2017 prices).

The Dutch government agreed in 2002 that the Netherlands would contribute USD 800 million towards the cost of developing the JSF (SDD). This has now been more or less paid in full. The euro equivalent of the amount paid is €830.5 million (in 2017 prices).

The Dutch contribution towards the cost of the operational test phase of the JSF (IOT&E) is was capped at a maximum of USD 37.5 million in 2014, when Australia joined the test phase,. The Netherlands has also bought two test aircraft for the test phase.

The Dutch contribution towards the cost of the production, maintenance, sustainment and the follow-on development (PSFD-MoU) of the JSF was capped at a maximum of €359 million (in 2006 prices) in 2006.

This means that the US is required to pay for any budget overshoots in relation to the development costs. Thanks to its role in the programme, the US is in a better position to control the level of cost.

The contribution for this long-term MoU is not paid in the form of a single lump sum, but in a series of instalments in line with the progress made by the manufacturers and hence in accordance with the invoices sent by the manufacturers to the JPO. The Netherlands regularly receives requests from the JPO (known as calls for funds) for the payment of the next contribution. The calls for funds made on each partner country are based on the country’s share in the programme.

How can contributions end up being higher or lower than originally agreed?

Although, in theory, each MoU sets a maximum figure for the contributions, the actual size of each contribution may end up being either higher or lower than originally projected. There are three reasons for this:

- Inflation in the US: the amounts are based on US prices in a given year (known as the ‘base year’: hence the term ‘base year dollars’). Due to the effects of inflation, certain amounts have to be adjusted to the prices in the year in which the expenditure in question is incurred (known as ‘then year dollars’). This applies particularly to long-term MoUs such as the PSFD MoU. The contributions towards the CDP and SDD phases do not change because the payments have already been made.

- Exchange-rate fluctuations: if it has been agreed that payment should be made in dollars, exchange-rate fluctuations may result in the cost as expressed in euros turning out to be either higher or lower than the dollar cost. For this reason, when we convert dollar payments into euros, we state the dollar-euro exchange rate used in our calculation. In the case of the SDS MoU, there is no risk of the cost ending up higher due to a higher dollar-euro exchange rate as the government has signed a forward exchange contract as a hedge against this risk. In other words, the requisite dollars were bought at the time when the MoU was signed.

- New agreements: the cost of an MoU for a partner country may also change as a result of new agreements among the partners. This applies, for example, to the OIT&E MoU. This was adjusted in April 2014 to take account of a new agreement on the extension of the operational test phase for the JSF. The three partner countries, i.e. the US, the UK and the Netherlands, had agreed to form a contingency reserve for the test phase. This had the effect of raising the Dutch contribution by €7.5 million. The cost of the IOT&E phase also changed when Australia decided to join the IOT&E phase.

Link with financial budgets?

The aggregate Dutch contribution to the various phases of the JSF programme. The phases of the JSF programme> is estimated to be approximately €1.74 billion. This includes the cost of buying two test aircraft. This figure does not include the actual cost of buying the JSFs.

The figure of €1.74 billion is not additional to the €4.5 billion agreed by the government under the financial framework as the maximum budget available for the acquisition of the JSF. Part of it is included in the latter figure. This is because certain forms of expenditure on the MoUs are included in the budget, whereas others are not.

Distribution of Dutch contributions over the MoUs

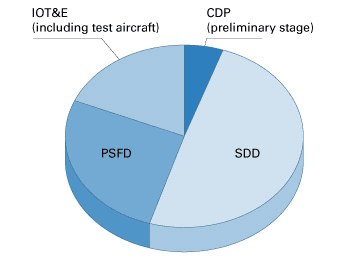

The following diagram shows the Dutch contributions agreed for each MoU almost half of the contributions are intended for the design phase (SDD); over a quarter for the production phase (PSFD), and just over one-fifth for the operational test phase (IOT&E), including the two test aircraft.

Audit of JSF programme exit costs

A debate arose in 2012 around the question of whether the Netherlands should continue with the JSF programme. At that point, the Dutch government had not yet decided to actually buy the JSF.

We were asked by the Dutch Ministry of Defence to examine the following three options:

- continuing as a partner in the programme (and the cost of doing so);

- withdrawing from the test phase only;

- completely withdrawing from the JSF programme.

We looked at the financial consequences of each of these options and their other implications.

The audit report explains how much it would have cost if the Netherlands had decided at that point to withdraw from the JSF programme, but nevertheless to replace the F-16 aircraft. Although it was possible to work out some of the resultant cost, a large part of the cost was not open to estimation. We concluded that the uncertainty surrounding the unknown costs was so great as to preclude any judgement about the financial cost of withdrawing from the programme.

We did not include in our calculations the investments that had already been made in the programme, as these were sunk costs that had already been incurred and would not therefore have made any difference to the analysis.

Withdrawing from the programme would not speed up the process of replacing the F-16, partly because of the time-consuming order process and partly because the other candidates were still in the course of development too.

The conclusion: we drew in our audit report was that, given the consequences in terms of functionality, time and money, a rational decision to withdraw from the JSF programme and purchase another aircraft off the shelf could be made only if the current criteria for the operational deployment of the Royal Netherlands Air Force were to be reviewed.

As each of the options had far-reaching consequences for the entire armed forces, we believed that the government needed to review its ambitions for the armed forces.

The second government under Prime Minister Mark Rutte subsequently asked the Minister of Defence to formulate a long-term strategy for the armed forces. This was set out in a policy document entitled ‘In the interests of the Netherlands’. The decision taken by the government as announced in this policy document was, firstly, that the Netherlands would continue with the JSF programme and, secondly, that the Netherlands would buy 37 JSF aircraft.