How long should it take?

The administrative burden in primary education

When asked about the main causes of pressure at work, primary school teachers put paperwork high on the list. But little is known about the administrative burden on primary school teachers in the Netherlands. There is no clear picture of the most demanding administrative tasks or how much time is spent on them. It is also uncertain who imposes the tasks, who benefits from them and what their purpose is. The minister and education professionals must answer these questions if they are to achieve a targeted reduction in the administrative burden. This audit represents a first step towards that goal.

This topic is also important with a view to the efficient use of public money. Teachers’ salaries account for most of the money the minister spends on education. The scarce time available to teachers should therefore be used as efficiently as possible, not on unnecessary paperwork. There are approximately 90,000 FTE teachers working in primary education in the Netherlands (source: https://www.ocwincijfers.nl/). If they all spent 1 hour per week less on paperwork, they would save 2,250 FTEs per annum. This additional capacity could be applied to relieve the teachers’ workload or improve the education provided to pupils. Reducing the administrative burden would therefore be of great benefit to both teachers and pupils.

Conclusions

Teachers considering leaving the profession because of the paperwork

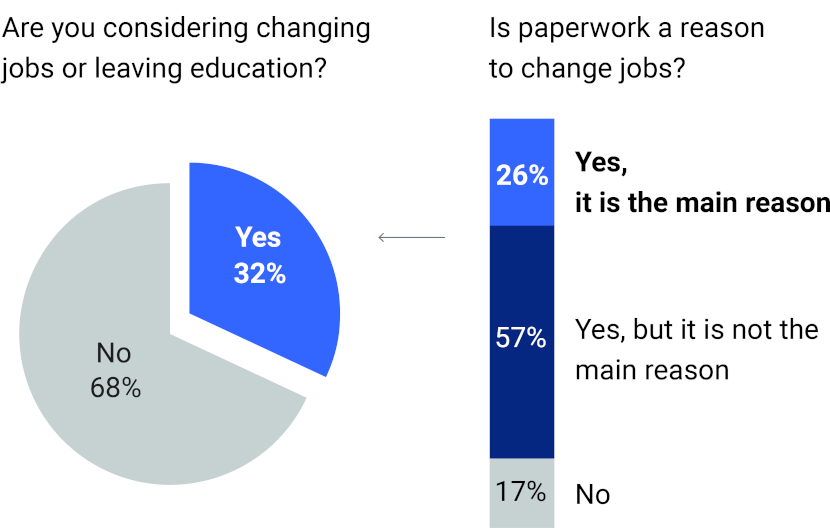

Our audit found that teachers thought the administrative burden was indeed a serious problem. A third of primary school teachers were considering changing jobs. Most of them thought the administrative burden was a reason or even the main reason to leave the profession. Although not all the teachers will act on their thoughts, the administrative burden can magnify the shortage of teachers.

Many teachers considering changing jobs because of the administrative burden

Paperwork burdensome because it costs so much time

The main reason that teachers consider paperwork to be a burden is that it costs so much time. On average, primary school teachers spend 5 hours a day in front of the class. Because primary classes need continuous attention, it is practically impossible for a teacher to carry out other tasks during those hours. They have another 3 hours a day for paperwork and other administrative tasks such as preparing lessons, checking schoolwork, consulting colleagues, organising trips and contacting parents. If the paperwork takes up too much time, these other tasks can be compromised, or the teachers have to work in their own time.

Teachers spend 6 to 8 hours a week on paperwork

On average primary teachers spend more time on paperwork in the Netherlands than in other countries on which data are available. The time teachers have to spend on paperwork is probably the reason that primary teachers cannot complete all their work during school hours.

Significant differences between individual teachers

The averages do not tell the whole story. The differences in the time individual teachers spend on paperwork are significant. This is because not all teacher work as quickly or as efficiently as each other. Some teachers are more proficient with a computer than others, or write information up in greater detail. These differences can be reduced if teachers learn from each other or if good agreements are made within schools.

Teachers with part-time contracts spend more time on administration

Besides individual differences among teachers, we found 2 other factors that make an important difference. The first is that teachers working part-time spend more of their time on administrative work. This is partly because of the time spent on handing over their work and coordinating with their part-time partner teacher.

Special needs pupils create additional administrative work

A second important factor for the differences among teachers is the number of special needs pupils in their classes. On average, teachers spend 15 minutes a week extra on administrative tasks for each special needs pupil in order to plan, coordinate and evaluate the extra assistance provided.

More special needs pupils, more time spent on paperwork

Teachers understand the benefits of paperwork but do the benefits outweigh the costs?

In general, teachers understand the benefits of their administrative work. Teachers and other education professionals explained to us why administrative tasks were necessary and even agreed with the reasons for them. Paperwork helps them inform parents and provide individual pupils with the support they need. Teachers also believe the information is used by the people for whom it is intended. The question is mainly whether the benefits of paperwork outweigh the time it costs. That time can only be spent once and other important tasks might be neglected.

Little paperwork required directly by law

There are virtually no direct government requirements regarding the administrative work teachers must carry out by law. The law, however, does have an indirect effect. It lays down, for instance, ‘open standards’ that schools must meet. ‘Open’ means schools themselves can choose the resources they use to meet the standards. A lot of administrative work at schools is due to open standards.

One open standard is that the education must be appropriate for the pupils’ development; another is that teachers must inform parents about their children’s progress. Schools organise administrative tasks to demonstrate that they meet these standards and the Inspectorate of Education checks the paperwork to ensure that they do.

The law’s impact on behaviour explains some of the administrative burden

Open standards effect the behaviour of schools and are a source of many administrative tasks. A prime example of this is the administration necessary to provide pupils with extra assistance. Here, too, however, little paperwork is required directly by law but schools have to perform administrative tasks to show that they provide the extra assistance required by law and that they meet the requirements. The legislator expects schools to offer pupils extra support themselves wherever possible and call in external assistance or special needs teachers only as a last resort. A consequence of this is that some schools record everything they do for their pupils so that they can later demonstrate that extra external assistance was necessary. Such behavioural effects and the resultant paperwork are not taken into account when laws are drafted.

Options to reduce the administrative burden

Scrapping rules is not a solution to the administrative burden in primary schools

A well-known political reflex to reduce the administrative burden is to look for pointless rules that can be scrapped. But this will not help primary schools. The legal requirements on teachers’ administrative tasks are few and far between and those that there are have a definite purpose. Furthermore, there is no guarantee that scrapping rules will actually eliminate the administrative burden. Teachers have not had to make pupil development plans, for instance, for many years, but nearly all the schools we visited were still making them because they had always done so.

Better cost benefit assessment needed at all levels: minister, schools and school managers

There are no simple solutions to reduce the administrative burden: there is not one single actor who can make a difference. Several parties, however, have a part to play, be it requiring less paperwork to be done, or making administrative tasks more efficient. Teachers could also be given more time for administrative work to ensure they do not neglect other important tasks or have to work in their own time.

The Minister of Education could make a more realistic estimate of the administrative burden that new policies impose on teachers. The minister should take account not only of the tasks required by new policy but also, and especially, the tasks schools themselves will organise for new policy. The minister should also make a more considered assessment of a measure’s benefits and the attendant administrative burden. When important goals such as the provision of more appropriate assistance or greater involvement of parents and pupils create paperwork that reduces teachers’ pleasure in their work, difficult decisions will have to be taken. Parliament has a right to expect the minister to make such an assessment when formulating new laws. As a co-legislator, parliament also has a responsibility to ensure that the assessment is made correctly. Members of parliament therefore have a duty to ask for more information if the cost-benefit assessment is not transparent.

The minister and the Inspectorate of Education could provide more guidance on how schools can meet expectations with the minimum effort. Schools value their freedom to organise administrative tasks but they are not entirely sure that they will be adequate. It would help schools if the minister and the inspectorate clarified what administrative tasks were not necessary and shared best practices on how tasks could be organised as efficiently as possible.

Schools themselves could do a lot. There are significant differences from one school to another in the amount of time teachers spend on paperwork. This means that there is potential for teachers to learn from each other. School managers could facilitate this by making time available for peer-to-peer learning. Schools themselves could assess the costs and benefits of administrative tasks more purposefully. There are reasons that schools perform many of the tasks but they cost time. Analysing the time taken for each task and the time teachers spend outside lessons could help prioritise administrative tasks.

School managers, finally, also have a part to play in reducing the administrative burden on teachers. Teachers regularly record information ‘just in case’, for example to avoid the risk that they later cannot explain why a pupil needed extra assistance or if there is a conflict with parents. By accepting this risk and reducing unnecessary paperwork, school managers would demonstrate their confidence in the school and its teachers. This, however, calls for a certain amount of risk appetite. School managers could also identify best practices and share them with other schools.