How much does the Netherlands pay into the EU budget and how much does it receive?

The EU member states finance approximately 92% of the EU budget. Since 2021, the EU has also borrowed money. Nearly 25% of the overall EU budget for 2021 consisted of loans. In 2021 EU revenue and expenditure totaled nearly €227 billion. The vast majority of these resources are used to achieve certain objectives, together with the member states. Most of the funds therefore flow back to the member states in the form of EU grants; nearly 60% of resources are spent on funds managed by the EU in conjunction with the member states. The size of the financial flows to and from the member states varies from one member state to another, depending largely on the relative prosperity of each member state and the objectives of the various EU funds.

A seven-year framework

The EU’s annual budget must be in keeping with the agreements made by the member states on the seven-year framework regulating the EU’s annual budget, known as the Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF). This framework sets the EU budget’s expenditure ceiling for a minimum of five but generally seven years an lays down how resources will be distributed across EU priorities, and how much each member state is required to contribute to the budget. The MFF determines to a large extent how much money member states will receive and contribute in the years ahead. Budget negotiations are complex and often protracted.

The European Council, consisting of the heads of state and government of the EU member states, agreed to a new MFF for 2021-2027 on 17 December 2020. They agreed to a package amounting to €1,074.3 billion. The Council’s decision followed a vote on the MFF in the European Parliament on 16 December 2020. The funds will be available as from 1 January 2021. The European Council and the European Parliament reached agreement on 18 December 2020 on the Next Generation EU plan to recover from the COVID-19 crisis. The recovery plan amounts to €750 billion. Together, these two agreements total €1,824.3 billion. Further information, is available here.

In 2021, 20% of the EU’s expenditure was related to the member states’ recovery and resilience plans (also known as RRF plans), an important component of Next Generation EU. The proportion of expenditure on the RRF plans is expected to increase further in the years ahead. The Dutch government expects to receive at least €4.7 billion from the RRF between now and 2026.

The financial consequences to the Netherlands of the new agreement are disclosed in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ budget for 2021.

An Own Resources Decision (ORD) is usually taken when a new MFF is agreed. The ORD lays downs provisions to determine how own resources are raised in order to finance the Union’s annual budget. The decision has to be ratified by the 27 EU member states. The ORD has been amended, partly because the contribution rebate system has also been modified and a new own resource has been introduced (a levy on plastic waste). In addition, the ORD provides for the loan system introduced by Next Generation EU. The own resources decision came into force on 1 June 2021 with retroactive effect to 1 January 2021. For the decision, click this link.

Annual EU budget

The MFF is implemented in an annual EU budget which has to be agreed on by the Council and European Parliament. The EU budget for 2023 is approximately €187 billion.

The Netherlands and the EU budget

The Netherlands’ contributions to the EU budget are estimated and accounted for in the budget of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In 2022 the Netherlands remitted €10 billion to the EU (after deduction of the compensation for collection of import duties). Its receipts through the funds under shared management totalled around €1.0 billion (source: Central Government Annual Financial Report, §3.4.1) and the EU sections of the ministerial annual reports of LNV, SZW, EZK and J&V.

In 2022 import duties amounted to €3,8 billion, over one third of the total Dutch payments to the EU (source: Central Government Annual Financial Report §3.4.1).

The Netherlands has been a ‘net contributor’ since the mid-1990s. It pays more to the EU than it receives from it.

For further information, see a study on this subject published by Statistics Netherlands in 2016

Which definition is used for the Netherlands’ net position?

In discussions about the MFF and the annual EU budget, one of the main topics is how the Dutch contributions to the EU and its receipts from the EU work out on balance. It is as a result of this calculation that the Netherlands is classified as a ‘net contributor’.

A factor complicating the discussions is that the Netherlands and the EU disagree about the size of this net contributor status. Although the Netherlands has referred only to the EU definition in recent years, the Dutch definition has regularly played an important role in negotiations in the past. The difference of opinion stems in part from the compulsory definition of the Dutch national contribution. The Netherlands includes the full value of its customs duties in calculating its contributions to the EU. These are duties that the EU obliges member states to charge on imports of goods from outside the EU. Due to the relatively high value of the goods imported through the port of Rotterdam, the Netherlands collects a large amount of customs duties. The European Commission does not consider these duties to be member state contributions, however. The Commission claims that they form part of what it refers to as ‘traditional own resources’. The member states located on the EU’s external borders levy import duties on goods imported from outside the EU, but do so – in the European Commission’s view – on the EU’s behalf. These member states are paid a fee (equal to 20% of the duties) to cover the cost of collecting customs duties (known as ‘perception costs’). It is for this reason that the EU does not include traditional own resources in its calculation of net contributor status. The Netherlands takes a different view and considers net customs duties, i.e. after deduction of perception costs, as forming part of its contribution to the EU as these are not resources generated automatically by community policies.

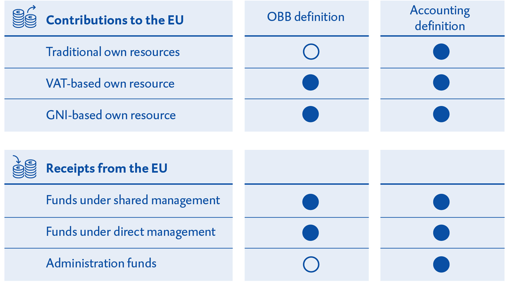

The figure shows the differences between the two definitions

At €3.0 billion, customs duties accounted for more than a third of Dutch contributions to the EU (source: Central Government Annual Financial Report, §3.4.1).

In fact, the Netherlands is a net contributor under both definitions, but the size of the net contribution differs considerably depending on the definition. In 2012, and again in 2020, the Netherlands Court of Audit showed how the calculations based on the two definitions panned out for the Netherlands (and the other EU member states). For further information, see section 2.2 of the EU trend report 2012 and Focus on the Netherlands’ net payment positon. The latter report includes the financial data to the end of 2019. For data on 2020 and 2021, click this link.